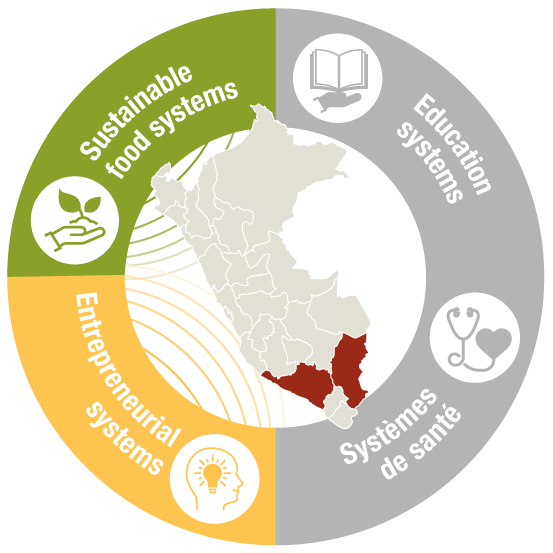

Peru

Arequipa Region

and Puno Region

2

partners

937

people affected in 2024

Louvain Coopération in Peru

Promoting sustainable food systems(ImpulSAD)

Our Objective

To develop and strengthen sustainable food systems and entrepreneurial dynamics within rural Peruvian communities, while improving access to food, natural, productive and environmental resources, as well as land and territory.

Our Actions

- Strengthening the resilience and environmental awareness of local actors through awareness-raising and the expansion of areas dedicated to environmental management (land use planning, sustainable management of natural resources).

- Agroecological transition for producers, including training, technical support and food diversification for women and farming families.

- Clean-up campaigns and reforestation activities in communal areas.

- Participation in research and experimentation on natural inputs to improve harvests.

- Support for green entrepreneurship and the structuring of cooperatives, through non-financial services to improve household incomes and strengthen local organisations.

- Development of sustainable small businesses, such as organic production, waste management or renewable energy, and promotion of short supply chains between rural producers and urban consumers.

- Economic, social and decision-making empowerment of women, with increased access to positions of responsibility in production units and better access to information and communication technologies.

Our impact

This project strengthens communities' adaptation to environmental challenges, improves food security and accelerates the agroecological transition. It also stimulates a sustainable rural economy through green entrepreneurship and contributes to women's autonomy in production, management and decision-making, thereby supporting more resilient and equitable territorial development.

The context of Peru

Peru is a highly diverse country with exceptional cultural, environmental and agricultural wealth. However, this diversity is threatened by economic models focused on agricultural exports and mining, which weaken the environment and increase social inequalities. Despite sustained economic growth in recent decades, large segments of the population – particularly rural and indigenous communities – continue to face poverty, food insecurity and climate vulnerability.

Agriculture and the economy

- 23% of Peruvians live off agriculture, which is the main source of income for 2.3 million rural families.

- This sector accounts for around 7.6% of the national GDP.

- Small producers, particularly in the Andes, struggle to market their produce (potatoes, quinoa, calafate berries, etc.) and access markets.

- Dependence on food imports is increasing, undermining food sovereignty.

Poverty and social inequality

- Nearly 40% of the rural population lives in poverty, twice as many as in urban areas.

- Rural women and indigenous populations remain particularly vulnerable, excluded from economic circuits, credit, training and decision-making.

- Despite strong growth between 2002 and 2013, the poor global economic climate has led to a marked economic slowdown and exacerbated inequalities.

Health and nutrition

- Child malnutrition affects between 30% and 40% of children in some rural areas.

- Obesity is on the rise and now affects 24.6% of people over the age of 15 in urban areas.

- The rate of anaemia among children under 3 is alarming: nearly 49% in rural areas.

- These contrasts reveal serious nutritional imbalances and unequal access to food resources.

Environment and climate

- Since 2002, the Andean region has experienced recurrent droughts that threaten food security.

- Peru is considered one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change in the Andean region of America.

- Soil degradation and biodiversity loss are increasing under pressure from agro-exports and mining.

Contact : info-aa@louvaincooperation.org

FAQ

The economy combines irrigated agriculture on the coast (fruit, vegetables, asparagus, blueberries), Andean agriculture (potatoes, quinoa, cereals, livestock) and agroforestry in the jungle (coffee, cocoa).

Industrial fishing (anchovies) depends on ocean conditions.

Mining plays a key role (copper, gold, zinc, silver, tin) with large-scale logistics chains.

Services and cultural and nature tourism complete the picture, with significant regional differences.

In the west, numerous short, seasonal coastal rivers flow into the Pacific, supporting irrigation in isolated valleys.

In the east, the major Amazonian tributaries (Marañón, Ucayali, Madre de Dios) facilitate the movement and supply of goods and services.

On the Altiplano, Lake Titicaca (shared with Bolivia) structures high-altitude agro-pastoral systems and local navigation. This diversity explains the contrasting logistics: trans-Andean roads, river ports, and, on the coast, irrigation and flood control works.

The Humboldt Current, cold and rich in nutrients thanks to upwelling, explains the paradox of a desert coastline and a highly productive sea (notably anchoveta, the basis of fishmeal and fish oil).

El Niño–La Niña episodes are recurring but irregular ocean-atmospheric variations (approximately every 2 to 7 years). During the El Niño phase (‘warm’ phase), the weakening of the trade winds reduces upwelling: surface waters warm up along the coastline, fish productivity declines and heavy rains, even floods, mainly affect the north coast.

During the La Niña phase (the ‘cold’ phase), the trade winds strengthen, upwelling increases, the waters cool and the sea generally becomes more productive, while coastal conditions tend to be drier (with possible opposite effects in the Sierra and Amazonia).

These cycles require authorities and industries to adapt their planning. In concrete terms, this means strengthening the protection and drainage of coastal valleys, maintaining dykes and bridges upstream of floodwaters, and adjusting fishing (schedules, quotas, temporary closures) to preserve both fish stocks and jobs on the coastline.

Ancient civilisations along the coast and in the Andes (Caral, pre-Inca cultures) preceded the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu), whose Andean road network, Qhapaq Ñan, connected the highlands to the valleys. This consolidated centres such as Cusco and linked agricultural circuits based on ecological zoning (terraces, canals, storage).

Colonisation reconfigured the space: political and economic refocusing on Lima, orientation of flows towards the Pacific coast and specialisation in extractive and port industries.

Today, these historical networks combine with the terrain to explain lasting contrasts in density, access to services and regional specialisation.

Located on the subduction zone between the Nazca and South American plates, Peru is one of the most earthquake-prone countries in the world.

Subduction earthquakes can generate tsunamis on the Pacific coast and affect coastal valleys. Further south, the Andean volcanic arc includes several active volcanoes (e.g. Sabancaya, Ubinas, Misti) that are capable of emitting ash, pyroclastic flows or lahars.

On the north and central coast, El Niño–La Niña episodes modulate rainfall: El Niño increases the risk of flooding, flash floods and debris flows (huaicos) in usually dry basins, while La Niña tends to exacerbate coastal drought. In high mountain areas, glacial retreat can destabilise morainic lakes and cause sudden drainage.

Preparation is based on a set of complementary tools: earthquake-resistant building codes and standards, urban microzoning, early warning systems for earthquakes, tsunamis, floods and volcanoes, maintenance of hydraulic structures (dykes, bridges, canals), evacuation plans and regular public drills, as well as land use management to prevent urbanisation of major river beds and unstable slopes.

On the coast, water is scarce and dependent on Andean inflows; in the highlands, slope erosion and the retreat of certain glaciers are affecting hydrology; in the jungle, deforestation and poorly regulated extractive activities are weakening ecosystems.

The responses combine slope management, rational water management, monitoring of land use changes and the promotion of activities compatible with conservation.

Peru is a country in South America, bordering the Pacific Ocean, with Lima as its capital.

Its territory is organised into three large complementary areas: the costa (desert coastline structured by irrigated valleys), the Andean sierra (high plateaus — puna —, inter-Andean valleys and high-altitude towns) and the Amazonian selva (forests and river networks).

This triptych shapes the distribution of the population and activities: urban densities and industry on the coast, agropastoral systems and historic towns in the Andes, logistics by waterways and agroforestry in the Amazon. It also translates into differentiated public policies on water, transport and access to services.

- Costa: irrigated agriculture, large urban centres and ports.

- Sierra: ecological zoning, terraces (andenes), trans-Andean mobility.

- Selva: river cities (Iquitos, Pucallpa), forest corridors and river logistics.

From coastal deserts to Amazonian forests and the Andes, Peru is home to a mosaic of ecosystems and a high rate of endemism.

Here you can find the Andean condor, spectacled bear, vicuña, puma, jaguar, giant otter, river dolphins, a wide variety of birds (macaws, hummingbirds) and orchids, as well as Polylepis forests at high altitudes.

The network of protected areas covers a variety of environments. Manu National Park (Andean Amazon) is home to exceptional biodiversity and rapid ecological gradients. Huascarán National Park protects the Cordillera Blanca, its glaciers, high-altitude lakes and high-mountain forests. The Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, in the heart of the Amazonian plain, safeguards vast floodplains (varzea) that are crucial for aquatic fauna and artisanal fisheries. Other major sites complete this ensemble (Tambopata, Cordillera Azul, Paracas).

Conservation challenges include deforestation and habitat fragmentation, illegal extraction (including mining in the Amazon), local overfishing, pollution and the effects of climate change (glacial retreat, hydrological changes). Responses include the expansion and effective management of protected areas, recognition of the rights and knowledge of local and indigenous communities, restoration of sensitive habitats (riparian forests, Polylepis), sustainable fisheries management and enhanced scientific monitoring to guide decision-making.

Agroecological approaches combine terraces (andenes) and careful water management (canals, infiltration, small reservoirs), crop diversity (potatoes, quinoa) and agroforestry in the selva (shading for coffee and cocoa, service trees). The aim is to stabilise yields in the face of uncertainty, reduce erosion and enhance local production (sorting, drying, quality).

Spanish is the common language, alongside recognised indigenous languages such as Quechua and Aymara (Altiplano), as well as Amazonian languages (Shipibo-Konibo, Asháninka, Awajún, etc.).

This diversity is expressed in ferias (markets), textiles (Andean weaving), regional music and dance, as well as in agrarian knowledge systems (terraces, canals, potato variety selection) that are part of the long memory of the territories.

Peru has a population of around 34 million.

The population is predominantly urban: nearly three-quarters of Peruvians live in cities, with a high concentration in the metropolitan area of Lima (more than ten million inhabitants) and a network of dynamic regional cities (Arequipa, Trujillo, Piura, Chiclayo, Cusco, Iquitos).

The demographic structure remains relatively young (median age around 30), in a context of demographic transition: fertility has declined in a generation, and life expectancy has increased over the long term.

These trends can be seen in sustained internal mobility (rural exodus from the highlands and the selva to the coast and Lima), the significant weight of the informal economy in urban employment, and territorial disparities in access to services (water, sanitation, health, education), which are more pronounced in the sierra and selva than in the coastal area.

Public policies are therefore focused on improving basic services, reducing inequalities and building the resilience of cities to climate hazards.

In the highlands, llamas and alpacas provide fibre, manure and, more locally, meat. Their adaptation to cold temperatures, steep slopes and low oxygen levels makes them pillars of pastoral systems. The vicuña, a protected wild species, produces a very fine fibre, with regulated shearing patterns. The quality of the fibres, artisan cooperatives and traceability support locally based incomes linked to regional and international markets.

Mines are a pillar of the Peruvian economy (copper, gold, zinc, silver, tin).

They drive logistics corridors and employment areas, while posing recurring challenges: water use in dry areas, territorial integration of sites, prevention of environmental impacts, relations with communities and stability of consultation frameworks. Their contribution to local development depends on downstream factors (industrial services, local purchasing, training) and the predictability of rules.

From irrigated coastal valleys to Andean terraces, from snow-capped mountain ranges (Blanca, Vilcabamba) to the Altiplano of Titicaca, to Amazonian forests (Madre de Dios, Loreto), the landscapes reflect a plurality of ecosystems and practices. Historic centres (Cusco, Arequipa), Andean routes (Qhapaq Ñan) and river towns in the selva make up a map where relief, water and history intersect.